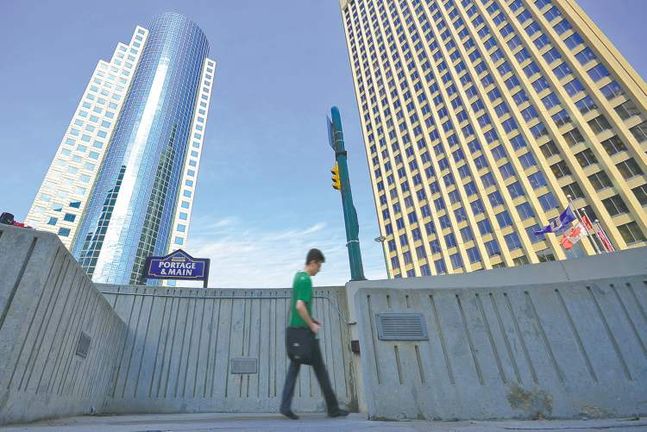

The barriers at Portage and Main enhance the perception of lack of safety and isolate that part of the downtown from others in the area.

At 10 o'clock this morning, there will be precisely 2,000 days left until the intersection of Portage and Main, Winnipeg's famous windy corner, can legally be opened once again to pedestrians. Whether it will open or not remains to be seen.

The story is well-known by now. With the construction of the Trizec building in the late 1970s, an underground connection was made to each of the intersection's four corners. In an effort to force people into the shops that lined the concourse, a 40-year agreement was signed with the six adjacent property owners that read, "The city agrees that it will not consent to any construction of a pedestrian crossing over or under any street" (at Portage and Main). Concrete barricades adorned with colourful flowers were installed and the intersection was sealed off to a generation of people.

Last month, the Canadian Institute of Planners nominated Winnipeg's windswept corner one of the "Great Places in Canada." The improbable announcement touched off a public discussion about the future of the intersection, with bloggers, television, radio and newspaper outlets all debating the subject.

Those who favoured the barricades argued pedestrians would be unsafe crossing with the high number of cars that pass through the intersection, yet traffic volumes are similar at Broadway and Main or Portage and Memorial, and pedestrians cross those intersections without incident every day.

The argument heard most often was adding pedestrians would significantly delay vehicular traffic, but with 11 stop lights and pedestrian crossings already in place along the one-kilometre length of Portage Avenue in downtown, it is unclear by how much.

To alleviate these safety and congestion concerns, cities around the world have implemented so-called scramble corners at similar intersections. Using this strategy, vehicles cycle through without pedestrians, then with all vehicles stopped, pedestrians are allowed to cross in every direction, including diagonally. This sequence eliminates the typical interaction between cars and pedestrians and only adds one minute to each traffic cycle.

Despite a fear of change, opening Portage and Main to pedestrians as part of a greater strategy to make Winnipeg's downtown a more walkable neighbourhood would have a significant positive impact on the city in many ways.

The number of people who spend each day working at Portage and Main is nearly equivalent to the population of Steinbach. If the intersection were a city, it would be one of the five largest in the province, yet few street-level amenities exist to support that market. Enticing even a portion of these people back onto the sidewalks might increase foot traffic to a level where the first three blocks of Portage Avenue no longer have more empty storefronts than the rest of its 14-kilometre length combined. Albert Street, an adjacent toothless grin of vacant lots, derelict buildings and empty retail units, might finally fulfil its potential as a trendy urban strip and connection point to the burgeoning Exchange District.

A closed Portage and Main currently acts as a physical and intellectual barrier in the downtown. The Forks, the East Exchange, Waterfront Drive, Stephen Juba Park and the river are all disengaged from the rest of the city because of this divide. As the Canadian Museum for Human Rights opens and the mixed-use residential development is constructed across from it, establishing pedestrian connections will become a significant opportunity to finally engage The Forks as part of downtown. Breaking down this barrier and establishing these neighbourhood relationships would make the ocean of surface parking lots along the rail line attractive to development as they become a bridge between these two areas.

Safety is always highlighted as a key impediment to our city's urban growth. Despite statistics that indicate downtown crime levels are no different than in other cities, the lack of people on Winnipeg's sidewalks creates an impression of insecurity, heightening the perception of crime. It is uncomfortable to be near Portage and Main in the evening because of the feeling of isolation the concrete barriers and empty sidewalks create. Opening the corner up would repopulate the area, providing strength in numbers and putting more eyes on the street to establish a greater feeling of safety and security for pedestrians.

Improved safety and enhanced walkability are vital ingredients in establishing a desirable urban neighbourhood that attracts residential development, widely accepted as the key to downtown revitalization. Governments currently offer incentives to entice this growth, but in the long term, the residential market must be self-sustaining. Opening Portage and Main as part of an overall scheme to increase walkability and improve the pedestrian experience is an important part of creating the desirable conditions that attract buyers to urban living and establish a competitive downtown residential market without subsidies.

The Canadian Institute of Planners' recognition of Portage and Main, even in its current condition, shows it is a place the story of which still resonates in the imagination of Canadians. With no other Winnipeg location holding that level of prominence, its current utilitarian function is a lost opportunity in a city that cannot afford to squander its few noteworthy attributes. Surrounded by many of the finest historic buildings in North America and most beautiful public art in the country, inviting people back to experience our most important public place would be a source of pride for tourists and Winnipeggers alike.

Reanimating Portage and Main with a pedestrian vibrancy would not only physically transform the heart of our city but it would hold great symbolic value, signalling to the world Winnipeg is a progressive community that has shifted its urban-design focus to people and neighbourhoods. Establishing a sense of place at the historic crossroads of Western Canada would be an expression of a modern, forward-thinking Winnipeg and with reverence to where Bobby Hull was once signed, a place to celebrate the Jets' first Stanley Cup victory.

Brent Bellamy is senior design architect for Number Ten Architectural Group.

bbellamy@numberten.com

Republished from the Winnipeg Free Press print edition September 3, 2013