The setting is an "open house" presentation in an elementary school gymnasium. Nervous architects stand in front of coloured charts and maps, their drawings intentionally vague enough to conceal how far along the design really is. An agitated city councillor tries to control an angry room as local residents in uncomfortable folding chairs cheer and jeer every sentence of a long-winded presentation. When given the chance to speak, each laments the loss of green space or a familiar view, invariably foretelling horror stories of increased traffic on their quiet streets.

From the Fort Rouge rail yards to a Waterfront Drive hotel, condominiums in Osborne Village and apartment buildings in North Kildonan, this scene has become an increasingly familiar one across Winnipeg as neighbourhood residents seemingly rally in opposition to every new construction proposal in the city.

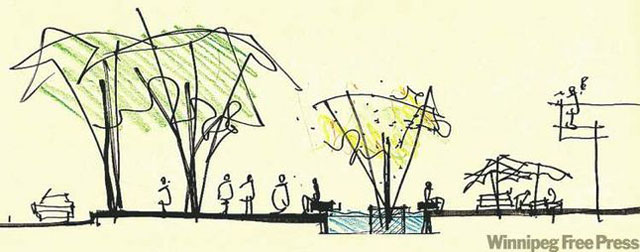

Winnipeg Free Press archives An artist's conception of a planned luxury hotel on the former site of the Alexander Docks. Some opposed the development on the grounds it would eat up green space and obscure views of the Red River.

Those looking on from the outside often brand these opponents to development as NIMBYs (not in my backyard). The NIMBY tag, unfortunately, is often used to dismiss opposition by reducing the debate to a catchphrase with a negative connotation, implying that no public concern is justified.

The prevailing attitude in Winnipeg has been that any development is good development, regardless of its long-term impact on the city's urban form. Public consultation is often seen as a roadblock to growth. Projects like the Whellam's Lane apartments in North Kildonan and the Safeway redevelopment in Osborne Village, however, became greatly improved designs in response to what some would label as NIMBY opposition.

Development advocates often say the solution to overcoming the NIMBY syndrome is to educate the public, believing opposition is based on ignorance of the issues.

This belief often leads to developers engaging the public at a point in the process when the key decisions have already been made. Neighbourhood consultation becomes an exercise in defending what has previously been decided, causing residents to feel that instead of being part of a collaborative design process, they are having the development imposed on them from the outside. Traffic studies and environmental-impact assessments presented to "educate" the public are dismissed as propaganda being used to justify decisions the public is unable to affect.

This scenario can lead to feelings of distrust taking root in the community, resulting in a combative relationship that is difficult to overcome, no matter how compelling the argument is for development.

The most effective solution to overcoming neighbourhood opposition is to include residents in the decision-making process long before specific proposals are made. When the discussions are two-sided and residents feel they are legitimate contributors to formulating long-term goals for their community, new development stands a much greater chance of gaining acceptance.

The Our Winnipeg Plan being developed by the city has set comprehensive long-range goals for future growth, but its most important contribution will likely be the secondary neighbourhood plans that grow from it.

Two neighbourhoods, Corydon-Osborne and South Point Douglas, are developing their secondary plans.

Through a series of design workshops and public open houses, the residents, businesses and community groups in these areas are establishing a collective vision for growth in their own communities. This planning process gives them an opportunity to be proactive and set clear guidelines. Secondary plans can outline shared goals for land use, densities, heritage assets and even set specific design guidelines for new projects such as height, setbacks and physical character.

Neighbourhood planning can promote and enable investment in a community as developers come to the table with a clear understanding of their opportunities and constraints. Investment becomes more attractive in these communities because developers know that if they adhere to the plan's direction and guidelines, projects can be streamlined by avoiding the costly effort of fighting public opposition.

A critical element in the long-term success of secondary neighbourhood plans will be political adherence to their recommendations. If developers are able to sidestep planning guidelines at the political level, community trust will be lost.

Winnipeg is a growing city, expected to reach a million residents within 20 years. Accommodating this growth exclusively as suburban sprawl on the city's periphery will inevitably lead to a fiscally unsustainable civic government, large infrastructure deficits and sharp reductions in city services. To be prosperous in the future, it will be necessary for Winnipeg to add density to existing neighbourhoods.

Every building ever constructed in Winnipeg has altered someone else's environment. Change is inevitable. Proactive neighbourhood planning through an inclusionary process allows residents to feel they have control over how their community manages this change. Genuine public consultation reduces NIMBY opposition, with more residents welcoming appropriate growth as an opportunity to make their neighbourhoods more vibrant, attractive and economically sustainable in the future.

Brent Bellamy is senior design architect for Number Ten Architectural Group. Email him at bbellamy@numberten.com

Republished from the Winnipeg Free Press print edition November 21, 2011 B4