By Franz Greenwood, Architectural Designer

It is now all too simple to raise money online to pay for that Dr. Who concept rap album you’ve been wanting to record, or perhaps that dream of building your very own 50ft electromechanical serpent. The relative ease of gathering a number of people together online who are willing to contribute time or money to a common cause, however uncommon, has helped everyone from basement tinkerers to NGOs not only see a demand for their product or project but fund it, test it and eventually realize it.

Technology has transformed every step of the architectural design process over the last several years. With the result being that the process itself has been accelerated, made more collaborative, and at times automated. Despite this, it bears to be seen how this advances our understanding of the end user experience. We can design buildings to be more efficient more efficiently, but how do these tools develop our understanding of beauty, a sense of space, buildings that truly work?

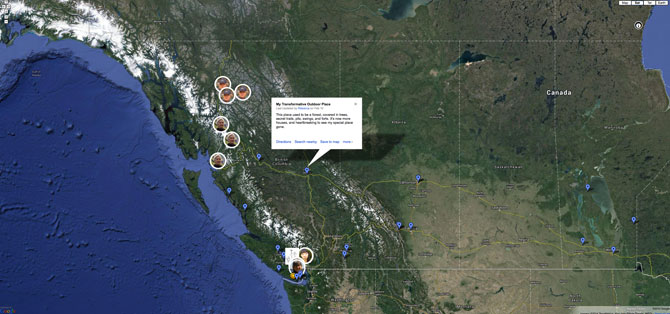

A January 18, 2014 episode of North By Northwest on CBC Radio 1 highlighted the work of Nick Stanger, a PhD candidate at the University of Victoria. He has developed a website that invites people to share their experiences of what he calls '(trans)formative places' by mapping out these places using a pinning a note on to a Google Maps style layout. Subjective though these accounts may be, Stanger’s expects this compilation of memory and encounters can be used to foster an 'emotional, physical, spiritual and ecological well-being.' As such the emphasis is on reconnecting with one’s natural surroundings through memory and shared experience.

Without delving too deep into the definition of nature in this case clearly architectural space is not the main focus of such an exploration but it very well could be. Though the study serves to better understand our relationship to nature, this approach to mapping experience could help the architectural profession assess how design can similarly impact us as people living in an urban environment and moreover how we can improve that urban environment.

Crowd sourcing may not be a familiar term to everyone, though by now few have managed to avoid the ubiquity of sites like Wikipedia. You don’t have to go farther than to simply hold up the website as perhaps the most famous example of the practice. Instead of having employees produce content for the site Wikipedia draws from the collective knowledge of all its users in order to offer a service. Simple. So, perhaps this can be used to enhance the architectural R+D process.

There are several crowd sourced website initiatives now that are currently approaching architecture and urbanism with the crowd-source format as a starting point, often using mapping and automation to create value and draw users.

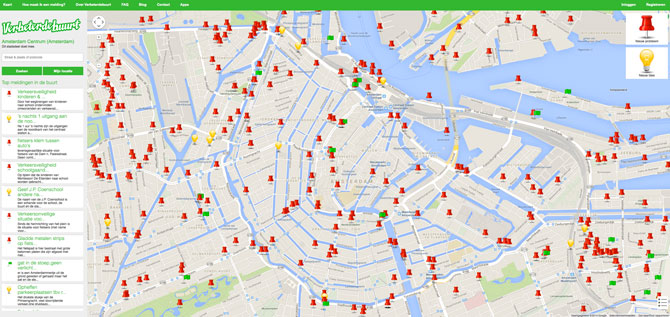

One remarkable example is Dutch website verbeterdebuurt.nl, which translates quite literally to ‘Improved Neighborhood.’ It allows city dwellers to voice their concerns about the quality of their environment through a map interface similar to the Transformative Spaces site (or google maps). Wishes, notes and points for improvement alert city officials to problem spots and in doing so generate a collective document of a neighborhood’s aspirations for itself.

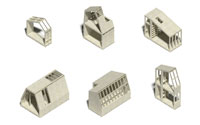

At the architectural scale there are similarly innovative projects. Wikihouse.cc is a site that provides people with the building blocks to manufacture their own house. The user downloads files that guide the manufacture of a series of plywood components that can be assembled by hand with just the minimum of basic tools. In addition to the predetermined design guidelines for the building system and preliminary design options, the site offers itself as an open tool box where people can contribute their own designs and improve upon the existing set of available components and ideas.

So what if there was a similar space for the expression and compilation of architectural experience? Perhaps we could learn how our designs play out post occupancy, how a design or building has had an effect on people, good or bad. Perhaps such a platform could even serve as a sounding board for community action or opinion before a building even comes into being.