Seeing forest for the trees: The bigger picture in the Lemay Forest debate

January 19, 2025

By Brent Bellamy, Associate + Creative Director

Originally published in the Winnipeg Free Press

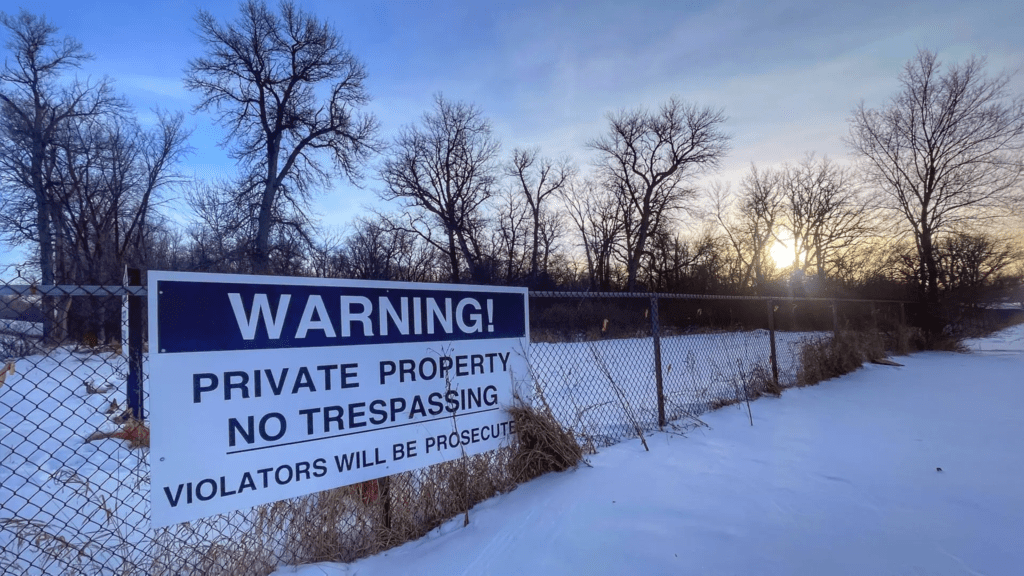

A little section of old growth forest — about the size of 30 soccer fields — nestled along the banks of a hairpin bend in the Red River has found itself at the centre of a political storm. Until recently, most people in Winnipeg had likely never heard about Lemay Forest in St. Norbert, but a standoff between residents and a developer who wants to cut down the trees has sparked debate about property rights and the role government should play in protecting our urban tree canopy.

What isn’t up for debate is the significant contribution trees make to the collective good in a city. Even when located on private land, their social and environmental impact is felt well beyond invisible property lines. On a macro scale, trees stand at the front lines of our collective battle with climate change. Even a small, 20-hectare forest such as Lemay can absorb enough carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to offset emissions from more than 5,000 cars every year.

With climate change increasing the frequency of high-intensity storm water events, urban trees are becoming vital in managing runoff and relieving pressure on municipal infrastructure. By absorbing storm water and increasing soil absorption capacity, Winnipeg’s trees prevent enough water from entering the city’s sewer system each year to fill more than 500 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

Winnipeg’s average temperature is projected to increase by almost seven degrees over the next 50 years, and the normal number of summer days that reach a temperature of 30 C will grow from 14 to 52. Trees will necessarily play a central role in making Winnipeg and all cities livable in the face of these changing conditions. An analysis of satellite data from 293 cities in Europe found that on hot summer days, tree cover can reduce the local surface temperature of a city by up to 12 degrees.

An urban tree canopy that moderates extreme temperatures can make cities more comfortable, and it can also save lives. A 2016 study in Toronto found that in extreme heat, an increase of two to three degrees can translate to an increase of four to seven per cent in the mortality rate.

Urban trees and forests further affect health conditions by improving air quality through the direct absorption of pollutants. A 2017 study for Environment Canada reviewed data across 86 Canadian cities and found the reduction of air pollution from urban trees saves the health-care system hundreds of millions of dollars per year and is responsible for the avoidance of 30 deaths and 22,000 incidences of acute respiratory symptoms annually.

Important connections have been found between trees and mental health in urban areas. When residents are exposed to well-treed neighbourhoods and forest settings, they typically produce lower measures of stress, anxiety, depression, anger, and fatigue, and increased measures of happiness and relaxation.

These powerful social and environmental impacts that trees have in Canadian cities are the reason St. Norbert residents are so upset about the potential loss of Lemay Forest. It’s also the reason cities across Canada are implementing bylaws to protect trees, even when they are on privately owned property.

In 2004, Toronto became the first major city in the country to develop a comprehensive set of rules to guide the management of privately owned trees and forests.

The city has set an aggressive goal of doubling its tree canopy over 40 years, and with 60 per cent of its trees located on private property, its private tree bylaw is an important tool to achieve this. The bylaw requires a permit to injure or remove any tree on private property with a trunk diameter of at least 30 centimetres.

To apply for a permit, an arborist’s report must identify the tree’s condition and reason for removal. Healthy tree removal is allowed to facilitate development, but the applicant must demonstrate it cannot be avoided and is required to pay $370 for every tree removed and plant three new ones in its place. This fee drops to $125 and one replacement tree if demolition isn’t construction-related.

Social and environmental impacts that trees have in Canadian cities are the reason St. Norbert residents are so upset about the potential loss of Lemay Forest. It’s also the reason cities across Canada are implementing bylaws to protect trees, even when they are on privately owned property.

Several other Canadian cities, including Ottawa and Vancouver, have followed Toronto’s lead by implementing similar policies. These bylaws are in place to manage and balance tree protection with the need to allow new development construction. Adding a cost for demolition and replacement results in developers being more diligent in saving mature trees as they design and lay out their projects.

The permit process also helps protect trees from being needlessly lost if a proposed development dies or changes before it reaches the construction phase. In the case of Lemay, such a bylaw would prohibit the demolition of the forest until a building permit for a new project is secured, which could be years away.

There is a common sentiment that private property owners should be able to do whatever they want with their land, but the reality is that in cities, all properties are subject to many layers of zoning and bylaws that restrict what can be done on them in the interest of the collective public good. In Toronto and other cities, trees are part of this consideration.

Hopefully, a resolution is found for Lemay Forest, but the debate should be seen as an opportunity for greater public dialogue about the social and environmental importance of urban trees and the effect they have on our health and quality of life. This incident can be the catalyst to a broader discussion about Winnipeg’s urban tree canopy and the role privately owned trees will play in its future.