Time for a plan on rail lands

July 23, 2023

By Brent Bellamy, Associate + Creative Director

Originally published in the Winnipeg Free Press

Ten years ago this month, the picturesque city of Lac-Mégantic, Que. was the site of Canada’s worst rail disaster since 1864.

Like Winnipeg, Lac-Mégantic has always been a railway town, and, like Winnipeg, its rail lines snake through the city’s residential neighbourhoods and through the centre of its downtown. When the runaway train of 72 tanker cars filled with crude oil from North Dakota came off its tracks, it was this proximity that made the incident so catastrophic, destroying 40 downtown buildings and killing 47 people.

Last February, headlines were made across North America when a derailed train in East Palestine, Ohio released an inferno of toxic chemicals into the air. Shortly after, with those dramatic images still in the news, a derailment on a Winnipeg overpass that closed McPhillips Street for several days shook the city, and the generations-old discussion about rail relocation resurfaced.

With these and other hazardous material train derailments making headlines over the last few years, it’s natural to focus on mitigating risk as the driver of any discussion about rail relocation in Winnipeg. It should also be seen, however, as an opportunity to reframe our city’s narrative and reset its trajectory into the future.

We only need to look as far as downtown Winnipeg to see how transformational this opportunity might be.

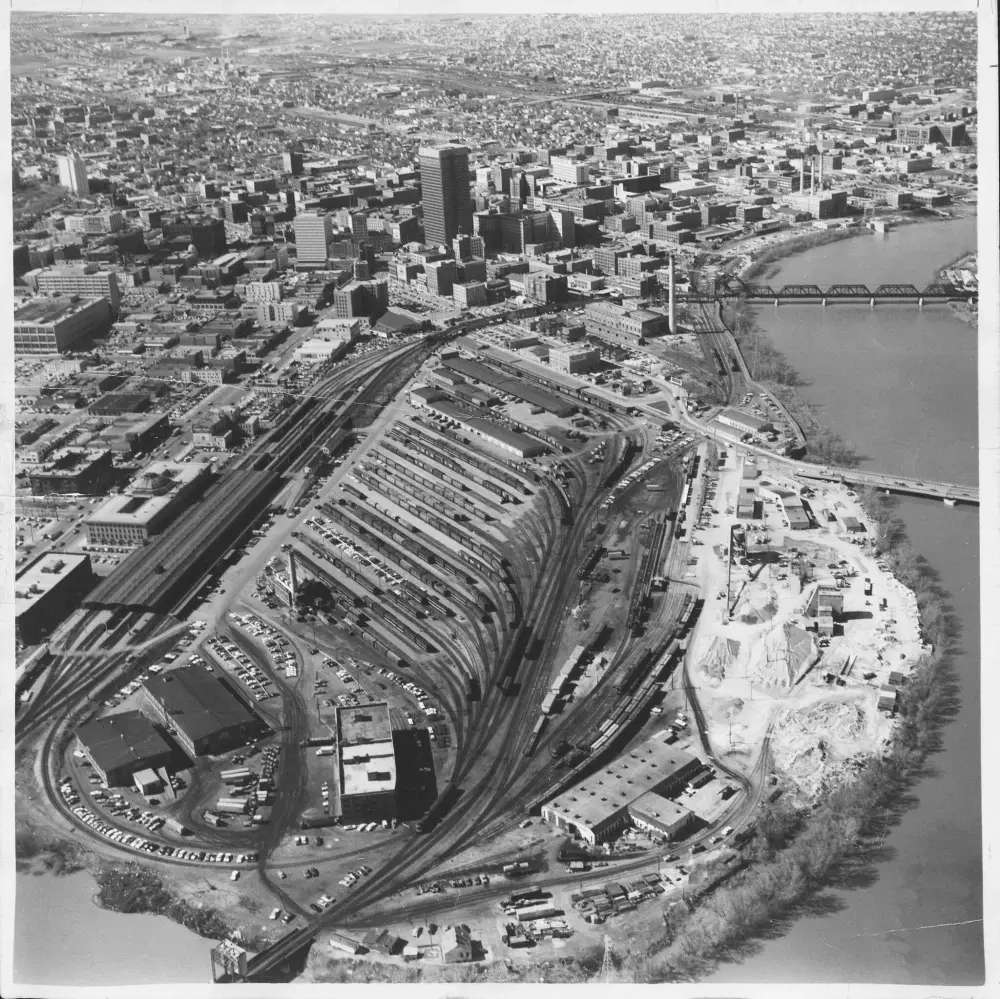

It’s difficult to imagine Winnipeg without The Forks, and it’s just as difficult to imagine it as a rail yard — brown and grey, with billowing smokestacks, and trains lined as far as the eye can see. If you would have told Winnipeggers in 1970 that the massive railyard at the junction of the two rivers was going to become the city’s crown jewel, and one of Western Canada’s most visited tourist attractions, they would tell you it could never be done. Canadian National moved on their own, but The Forks is a dramatic example of how a city can be transformed when rail yards are re-imagined.

Canadian Pacific’s Yards in the North End are so large that redeveloped into a medium-density, mixed-use neighbourhood, it could accommodate the population of Steinbach, Manitoba. A new urban neighbourhood of this size could bring an entirely new centre of gravity to the city. Consider the impact Bridgwater has had on Winnipeg, and then imagine how different that impact would have been, had it been built only a few kilometers from downtown. A new urban community could weave together historically disconnected neighbourhoods, and inject new investment, business, employment, and recreation opportunities into the urban core. It could be a catalyst for renewal across the inner city, enhancing and supporting existing local businesses and community services, while strengthening public and active transportation networks across the area.

In the recent election, Mayor Scott Gillingham made a campaign pledge to study rail relocation, stressing that it doesn’t have to be an all-or-nothing proposal. A comprehensive analysis might find smaller moves with high impact.

The BNSF rail line and yard that stretches across River Heights might be an example of this opportunity. The space it covers would be large enough to create homes for 6,000 people in a medium-density neighbourhood of townhouses, and three- to four-storey apartment buildings. This would increase the population of River Heights by 30 per cent, providing access to the neighbourhood for new families using existing amenities such as schools, parks and community centres, bolstering support for local shops and businesses, and providing incentive to improve transit service. Such moves represent an opportunity to increase the city’s population without expanding its overall footprint, reducing the amount of new infrastructure needed to support that growth.

A rail relocation study might identify lines that can be moved, even if the yards cannot. Imagine how The Forks and downtown might be more seamlessly integrated if they were not separated by a raised track. Minneapolis reclaimed its rail lines to create a network of active transportation and rapid transit corridors that have become catalysts for development driven by public demand to live near the desirable new quality-of-life amenity.

We have been talking about rail relocation in Winnipeg for decades, but without studying the idea, the conversation is quickly shut down by its daunting scale and cost. In a city so significantly impacted by the presence of railways, it seems almost negligent not to be fully informed about the opportunities and constraints they represent. A study would consider the balance between infrastructure costs like underpasses and bridges, with the cost of new railway infrastructure. It would evaluate economic benefits, including job creation, taxation growth, and urban renewal, and identify the long term social and environmental impacts of significant infill growth.

A comprehensive analysis might also be a win for the rail companies, revealing efficiencies and synergies that reduce their footprint and impact on the city. In an industry where time is money, locating at a place like CentrePort, integrated into a multi-modal inland port, instead of trudging through a growing major city under speed restrictions, might be a desirable business advantage.

The tools for Winnipeg to pursue the idea exist under the Railway Relocation and Crossing Act. Under this legislation, the federal government will pay for half the cost of a study, and if approved strategies are executed, it mandates the cooperation of the rail companies, and funds up to half the cost of implementation.

Rail relocation is a big idea with seemingly insurmountable challenges, but great cities don’t hide from big ideas, they engage in inclusive public dialogue and move forward with informed decision-making, backed by comprehensive research, study and planning.